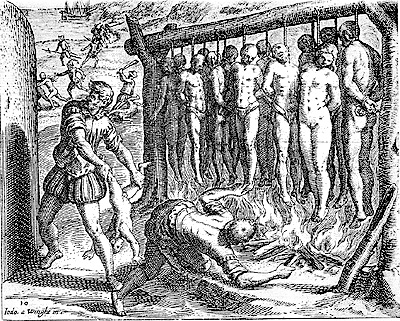

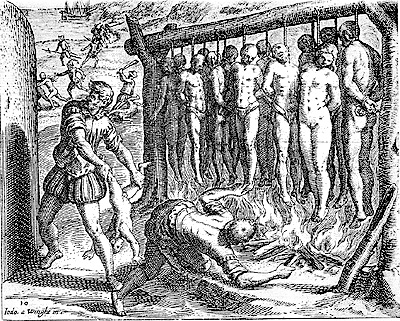

Bartholome Las Casas, Brief Report on the Destruction of the Indians

(illustration by Theodore De Bry, 1598)

Inventing Columbus and the Black Legend

1)

Felipe Fernandez-Armesto, "Columbus-Hero or Villain?" (May 1992)So which was Columbus: hero or villain? The answer is that he was neither but has become both. The real Columbus was a mixture of virtues and vices like the rest of us, not conspicuously good or just, but generally well-intentioned, who grappled creditably with intractable problems. Heroism and villainy are not, however, objective qualities. . . In images of Columbus, they are now firmly impressed on the retinas of the upholders of rival legends and will never be expunged. Myths are versions of the past which people believe in for irrational motives- usually because they feel good or find their prejudices confirmed. To liberal or ecologically-conscious intellectuals, for instance, who treasure their feelings of superiority over their predecessors, moral indignation with Columbus is too precious to discard. . . .

Thus Columbus-the-hero and Columbus-the-villain live on . . . no argument can dispel them, however convincing; no evidence, however compelling. . . . For one of the sad lessons historians learn is that history is influenced less by the facts as they happened than by the falsehoods men believe.

2) T. S. Floyd, The Columbus Dynasty (1973)

The issue of Spanish cruelty to the Indian seems to have acquired even more distortion in recent years than it commonly carried, having become entangled with racism, modern ideas of liberty, and other notions inappropriate to the historical context.

3) Noble David Cook, Born to Die (1998)

The Black Legend was firmly rooted at the core of European nationalism by the late sixteenth century. It was commonly believed that the evils perpetrated on innocent and ill-armed natives by the Spaniards led to the natives’ precipitous disappearance. There was no reason to invoke other causes. . .

At critical junctures the dusty bottle of the Black Legend has been uncorked and its thick venom released with predictable regularity at each commemoration of a major anniversary of the historical confrontation. . .

Another consideration that the conquistadores and the priests with them had to face was that somebody in the New World had to do the tilling, the digging and the carrying. Only the Indians were numerous enough for the tasks at hand. So the encomienda was invented, by which Indians were entrusted to Spaniards who were duty-bound to provide priests who would catechize the Indians--and, incidentally, the Spaniards wouldmake the Indians work. . . .

Of course excesses resulted. There were Spaniards who, in their greed for gold, worked their Indians to death, and Spaniards sometimes committed inexcusable atrocities. There were provocations by the Indians, who did tend to slide back toward their old religion, which involved idolatry, human sacrifice and cannibalism. . . .

Las Casas chose to attack this situation in a typically Spanish way: through unrelenting negative self-criticism. . . He repeated and magnified every story that he heard about Spanish cruelty. He deplored and damned every Spanish punishment of the Indians. He wildly exaggerated the number of Indians oppressed (up to forty million) and the geography involved (making Hispaniola larger than Spain). And Las Casas initially focused his vituperation upon Hernan Cortes. . .

1) Washington Irving, History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus (1828)

The imperfect state of science at the time. . . was still impeded in its progress by monastic bigotry. . . . Columbus was assailed with citations from the Bible. . . . To these were added expositions of various saints and reverend commentators. . . . A mathematical demonstration was allowed no weight, if it appeared to clash with a text of scripture, or a commentary of one of the fathers. . . . Columbus, who was a devoutly religious man, found that he was in danger of being convicted not merely of error, but of heterodoxy. . .

Such are specimens of the errors and prejudices, the mingled ignorance and erudition, and the pedantic bigotry, with which Columbus had to contend. . . .

2) John W. Draper, The History of the Conflict between Religion and Science (1873)

The antagonism we thus witness between Religion and Science is the continuation of the struggle that commenced when Christianity began to attain political power. . . . The history of Science is not a mere record of isolated discoveries; it is a narrative of the conflict of two contending powers, the expansive force of the human intellect on one side, the compression arising from traditionary [sic] faith and human interests on the other. . . .

Faith is in its nature unchangeable, stationary; Science is in its nature progressive; and eventually a divergence between them, impossible to conceal, must take place. . .

3) General History for Colleges and High Schools (1891)

The sphericity of the earth was a doctrine held by many at that day [Columbus’s]; but the theory was not in harmony with the religious ideas of the time, and so it was not prudent for one to publish openly one’s belief in the notion.

4) A. D. White, A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom (1896)

As to the movement of the sun, there was a citation of various passages in Genesis, mixed with metaphysics in various proportions, and this was thought to give ample proofs that the earth could not be a sphere. . . .

Many a bold navigator. . . trembled at the thought of tumbling with his ship into one of the openings into hell which a widespread believe placed in the Atlantic at some unknown distance from Europe. This terror among sailors was one of the main obstacles in the great voyage of Columbus. . . .

The warfare of Columbus the world knows well . . . . even after he was triumphant, and after his voyage had greatly strengthened the theory of the earth’s sphericity. . . the Church by its highest authority solemnly stumbled and persisted in going astray. . .

5) F. S. Marvin, "Science and the Unity of Mankind" (1921)

The sphericity of the earth was, in fact, denied by the Church, and the mind of Western man, so far as it moved in this matter at all, moved back to the old confused notion of a modulated "flatland," with the kingdoms of the world surrounding Jerusalem, the divinely chosen centre of the terrestrial disk.

6) J. B. Bury, The Idea of Progress (1920)

In discarding medieval naivete and superstition . . . men looked to the guidance of Greek and Roman thinkers, and called up the spirit of the ancient world to exorcise the ghosts of the dark ages. . .

7) Jeffrey Burton Russell, Inventing the Flat Earth: Columbus and Modern Historians (1991)

Educated medieval opinion was virtually unanimous that the earth was round, and there is no way whatever that Columbus’s voyages even claimed to demonstrate the fact. The idea that "Columbus showed that the world was round" is an invention. . . . Despite the work of modern historians of science, the Error continues to be almost as persistent as in the educated mind as it was nearly a century ago. . . .

What can the Flat Error teach us about human knowledge and our own worldview? First, historians, scientists, scholars, and other writers often wittingly or unwittingly repeat and propagate errors of fact or interpretation. No one can be automatically believed or trusted without checking methodology and sources. Second, scholars and scientists are often led by their biases more than by the evidence. . . .

Finally, fallacies or "myths" of this nature take on a life of their own. . . . For example, it has been shown that "The Inquisition" never existed, but that fallacy, like the flat earth fallacy, is part of the "cycle" that includes the Dark Ages, the Black Legend, the opposition of Christianity to science, and so on. The cycle becomes so embedded in our thought that it helps to form our worldview in ways that make it impervious to evidence. We are so convinced that medieval people must have been ignorant enough to think the world flat that when evidence is thrown in front of us we avoid it. . . . Thus our worldview is based more upon what we think happened than what really happened. A shared body of "myth" can overwhelm reason and evidence. . . . Caution is called for, to put it mildly.