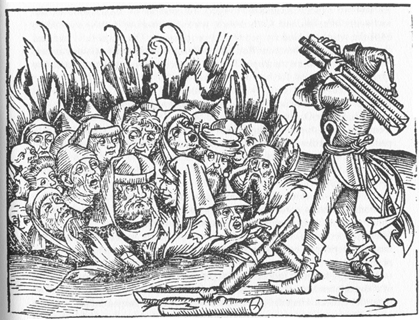

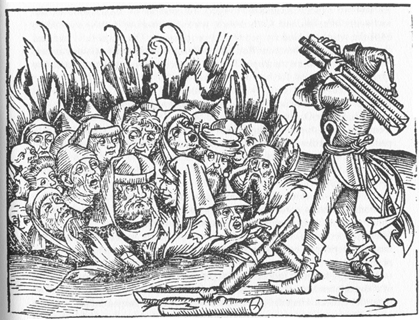

Burning of Jews (German woodcut, 1493)

Plague came from poisonous clouds or miasmas arising from the earth, some said. Conjunctions of the planets, volcanic eruptions, earthquakes and comets were blamed. . . . Dogs and cats (but never rats) were killed for spreading the plague. Drunkards, gravediggers, strangers from other countries, beggars, cripples, gypsies, lepers, and Jews were all tortured and killed. . . . Jews were tortured into confessing that they had poisoned wells or performed black magic. There was no escape. . . . .

No society suffering a loss of one-third of its population could function effectively. . . . So it was in the world of the Black Death. The foundations of society were gnawed from under it by rats. . . . The manorial system now broke down in large part because the shortage of manpower caused by the Black Death gave those workers remaining much greater bargaining power; they could become free laborers, earning the best price for their labor at all times. . . .